Research visit to the „Galton Papers“, University College London, Special Collections, April, 2015.

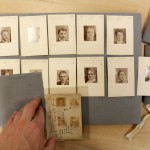

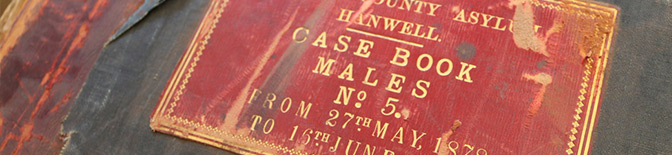

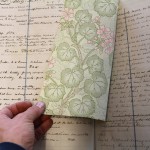

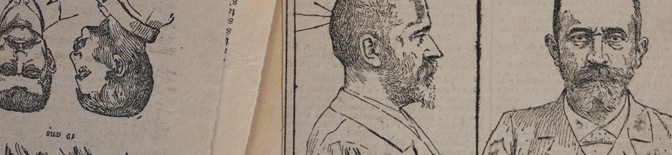

The „Special Collections“ of University College London are housed in the central library of the University. Only library card holders can enter, so a member of staff picks me up at the high-security entrance gate. After a hike through corridors, I am let to a room where on a library cart a huge pile of boxes and folders waits for me. This is quite a lot of stuff, and I have only ordered the material that seemed to be essential. Galton was an avid collector and everything seemed to be of interest: from letters to photographs, notebooks and articles, envelopes and scraps of paper. This is as much a heaven as a nightmare for a researcher like me. Here I will spend the next days, sifting through the material. The collection is well arranged and a considerable part of the material on and by Francis Galton was digitised recently. But especially with photographs and notes, it is important to consult the originals. To order and categorise the photographs, for instance, Galton used a form of binding. These small booklets that resemble flip books and that could be described as preliminary stages in the production of composite portraits. Often there are notes on the back of the prints, for instance, the remark: “This man’s nose spoils the composite.” Also the notebooks and letter books can be accessed as originals.

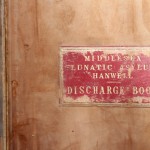

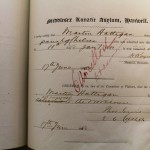

The material kept in the collection leads to further London museums and archives where information on Galton’s photographic practice is kept, such as the Metropolitan Archive, the Bethlem Museum and Archive, the Huxley Collection at Imperial College and the National Archives.