Research visit to the “Espace photographique Arthur Batut” & the Arthur Batut Collection, Labruguière, France, April 2014.

A narrow, winding road takes us through fields and woods, up and down the slopes of the “Black Mountains“, this is a harsh landscape, the climate much colder than at the coast – the trees are not in bloom jet. At the foot of the Mountain, the Arthur Batut Museum is secluded in the small village of Labruguière in the French Pyrenees. The museum is however not as idyllic, a quite impressive, newly erected municipal building next to the central roundabout. It houses the museum and archive on the 19th century French photographer, who is known as a precursor of aerial photograph, as well as for his experiments with the composite technique, the superimposition of portraits, he further developed, following the example of his Victorian contemporary Francis Galton.

Laura Falcetta already waits for us and leads us into the building of which a large room in the ground floor is dedicated to the Museum. Along with prints and instruments from the Batut collection, the small but well-designed exhibition presents instruments and artefacts from the history of photography. The museum however also shows temporary exhibitions of contemporary artists, whose works show connections to the permanent exhibition. In two small, but packed adjoining rooms, the collection of photographs, instruments and documents on the 19th century photographer is kept.

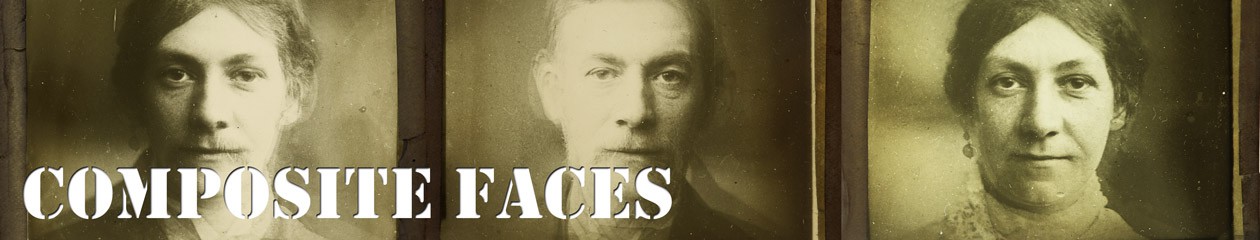

Laura shows me some folders that contain historical prints of Batut’s composite photographs and in many cases the individual portraits. Batut chose not to conceal his sources, in most of his products the individual portraits of men and women, often in their traditional clothes, are displayed alongside the final composites. Unlike Galton, who resorted to already existing portraits from prisons, schools, hospitals, Batut produced all of his material himself on his tours through the adjoining areas, but also as far as northern Spain and Barcelona. I could see about a number of composite portraits, their subject however does not vary as in the case of Galton, who used the technique to visualise phenomena such as criminality, illness, beauty, health and family resemblance. Batut’s use of the technique remains strictly “ethnographic”, his aim is to show the typical appearance, or average physical characteristics of the groups of people settling in the Pyrenees. In a publication on the technique, “La photographie appliquée à la production du type d’une famille, d’une tribu ou d’une race” (Paris: 1887), he contradicts the claims of Galton’s to use the composite technique on non-visible, inner characteristic, but stresses its value in his ethnographic visualisations of physiognomic traits. Here Batut follows the model of ethnography and visual anthropology of his time, which made extensive use of the medium of photography to depict and classify physical appearances of tribes, cultures, races. These examinations were mainly conducted in the European colonies to describe, typify and eventually rule the “new subjects”. Batut however deals with the rural French inhabitants, his neighbours, and in this respect his work could be seen as a form of early European ethnology. When he portrays a group of charcoal burners in the “Black Mountains”, he takes the photographs as part of what could be described as fieldwork. But the portraits are not used to prove their “subject’s” deficiencies, or even claiming their subhuman status, Batut uses the material to show physiognomical resemblance in the families and village communities. This attitude also shows itself in the composite portraits of the typical inhabitant of his hometown Labruguière and his family. The commissioned work for the typical woman of Sémalens furthermore provides the nonjudgmental gaze with a celebratory note. The composite portrait in this case was to be used as an example for the sculpture of Rose Barreau, a local hero in the French Revolution. Her “lost” appearance here was supposed to be replaced by an ideal, the beauty of the average female inhabitant of the village. Here again connections to the work of the technique’s founder, Francis Galton, become obvious, who not only used the visual typfication as a derogative means, but also worked on the visualisation of ideals, such as “health” and “beauty”. Still, also in Batut’s use of the composite technique, the aim is the visualisation of the invisible, the examination of characteristics that go beyond the visual realm. In this respect, the composites can be read in relation to visual arts, and, as the publication “Arthur Batut: Regards d’un humaniste photographe” by Serge Nègre and Sylvie Desachy suggests, in relation to the contemporary school of French Impressionism.

The archive provides insights into the production processes and, just like in the negatives of Francis Galton that are kept in the Galton Collection, University College London, in Batut’s photos intermediate stages can be found. From the original negatives details were enlarged, which were then used as source material for the production of the composites. Batut however in many instances seems to have worked more thoroughly than Galton. He often works with a larger set of visual data and there is no evidence of him having excluded individuals from his superimpositions. Furthermore, it is not the inner nature, the subhuman or “übermensch”, Batut seems not to have had in mind. Rather than differences and extravagant, telling physiognomies, his composite portraits show similarities and averages.