Research visit to Bedford and the collection of the earliest preserved judiciary photographs of Britain, Beds & Luton Archives and National Archives, London, July 2014.

Bedford station emits a small town atmosphere – a relive after the hectic London streets. I start walking in the direction where I expect the town centre and ask some people for the way to my hotel. It turns out to be more difficult than expected, but I meet an elderly man who is happy to help and join me. He tells me that this weekend there’s the big river festival. While we are walking – as it later turns out in the wrong direction – we get to talk about the city and he shows me some landmarks.

Turning a corner, we are suddenly facing the prison complex of Bedford – this is the place where the first British judiciary photographs were produced in the nineteenth century. The history of Bedford Prison dates back to the 10th century and the current prison was built in 1801, it has been expanded in 1840 and in 1990 when a new block was added. In the early nineteenth century state of the art prison included a turnkey’s lodge and cells for different convicts such as debtors and felons. Penal work was mandatory and a system of solitary confinement and silence was severely enforced. Meals were taken in the cells and also during work hours on the treadmill prisoners were kept separate. In 1840 the goal was enlarged and houses for the governor and chief wardens were attached.[1] Just recently, in 2012, it was revealed that the institution has the highest suicide rate of all English and Welsh prisons.[2] We walk on and when getting closer to the riverside the quiet atmosphere disappears. We walk past large crowds of people amusing themselves with music, food and drink. And there it is – my hotel – right in the epicenter of the festivities, fortunately my room faces the backside.

Early the next morning I walk to the municipal building where Beds & Luton Archives are located. The nice staff leads me to a table in a well lit room and produces a large, leather bound volume that holds the prison records and portraits of Bedford Prison. The pages seem to have been bound at a later stage, since neither the dates, nor the registry numbers are consecutive, but the almost 200 entries are in a roughly chronological order and were produced between 1859 and 1876.

In the late 1850’s, the Prisoners Governor of Bedford, Robert Even Roberts, was among the first who started to use photography in criminal identification. The earliest preserved portraits of prison inmates from the collection date from 1859. In his reports to the Prison Authorities he proposed photography as a suitable means in the identification and detection of criminals, but also claimed its utility in the determent of crime:

The application of photography as an agent in discovering the antecedents of criminals, especially tramps and strangers, is most unquestionably a very useful auxiliary and in my humble opinion should be brought into Prison use generally. I have had recourse to it now for nearly two years, and am daily convinced of its great utility, and what renders its application still more beneficial it is distasteful to prisoners, in as much as they invariably dread exposure, and once their photograph has been taken they are unconscious of the use that is made of it, and therefore it cannot fail to act as a deterrent to crime. As regards its application in this prison, I have succeeded in tracing the previous histories and characters of several of our inmates, without this aid the court would frequently have been in utter ignorance of their antecedents and old offenders would have escaped with much lighter punishment than they received.[3]

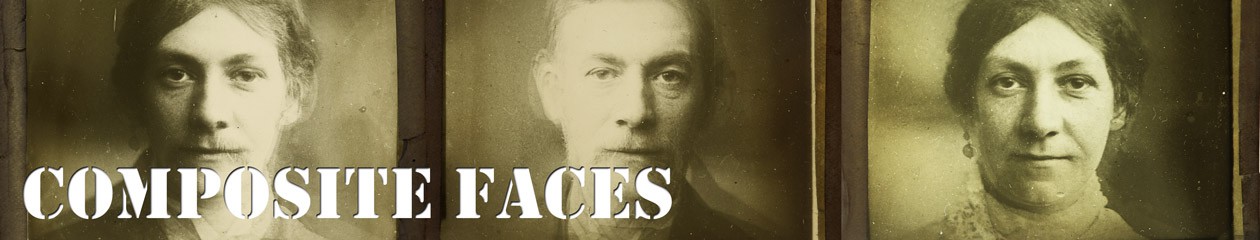

In the Bedford collection the development of a new visual language for the depiction of criminals can be traced that moves gradually away from 19th century civic studio practices towards special ways of depicting the criminal face. The quest for visually imprinting the context into the portraits lead to astonishing results and specially designed studio equipment, such as a painted backdrop showing a prison scene. From a tiled corridor a steel-enforced, but open prison door leads into a cell, light is emanating from the interior – one can easily imagine a circular layout and a central watchtower as it was proposed by Jeremy Bentham in his architectural proposal for the panopticon. This depiction of the inmates in front of the open door of a prison cell adds another narrative layer and alludes to ideas of a just and clean, socially condoned form of punishment in the modern penal system. This specific visual practice was abandoned at a later stage, already in the later photographs of Bedford collection. However, also these peculiar results were part of the quest for an easily understandable iconography of the depiction of the criminal in early judiciary photographs.

But the collection in also interesting in respect to the information that was collected alongside the portraits in the large bound book. The double framed portrait sits in the center of the page, but the printed forms assign numbers and dates to the inmates and note names and aliases, the offences and sentences, as well as previous convictions and offer space for additional remarks. The personal description is however not entirely reliant on the photograph: information such as age, height, hair colour, eye colour, complexion, shape of the face, weight, profession, place of birth, residence, marital status, religious denomination, and ability to read and write, as well as special marks and remarks are noted next to the portrait. In a few cases even comments on the photographs and the use of the medium in criminal identification are noted, such as remarks that the Prison Governor was able to establish the true identity of a convict through photography. In a later report after establishing the practice of photographic recording, Roberts emphasizes:

“Photography is highly approved of as inexpensive, effective and wholly free from objection as a possible means of identification, numerous discoveries of old offenders through its agency have been made in this prison, without which nothing whatever would have been known against them.”[4]

The register also documents the seemingly widespread practice of sending around prisoners to other penal institutions. On the upper right corner the date of release or more often the convict’s next destination in the penal system. Some individuals that were registered and photographed in Bedford were sent on to Pentonville Prison and can be traced down in the registers of Pentonville’s, which are kept in the National Archives London. In Pentonville again they were registered and photographed. Some photographs taken in Pentonville Prison were later made available to Francis Galton by the director of convict prisons Edmund Du Cane to conduct experiments with composite portraiture. Due to missing individual portraits and Galton’s request of anonymisation a final prove is difficult, but, judging from the posture and clothing, it is very likely the source images used for the “criminal composites” were taken in the 1870’s in Pentonville. So it seems possible that individuals who were first photographically registered in Bedford might have become part of the composites. Furthermore, the experiments with composite portraiture only became possible through the systematization of the depiction of convicts in frontal expressionless portraits that was, in the British case, originating in the photographic practice in Bedford.

[1] http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42369

[2] http://www.bedfordshire-news.co.uk/Local-jail-tops-league-inmates-suicide-rates/story-21720762-detail/story.html

[3] QGR1/43 Prison Governor’s (Robert Evan Roberts) report to the Michaelmas quarter sessions 1860, Beds & Luton Archive, Bedford.

[4] QGR 2/3/1/7 Prison Governor’s (Robert Evan Roberts) report to the quarter sessions Assemblage, Michaelmas Sessions 1863.